We are going through a special period when governments have been digging deep into the artistry of off-balance sheet financing via central banks treasury bills to bail out the technical insolvencies of banks. Despite this massive lender of last resort help, today there is a plethora of investment analysts notes circulating with undisguised sarcasm and cynicism about government finances.

Even I am amazed at how shamelessly the financial markets can turn to savage governments that are doing so much to buy them survival time through the credit crunch and recession!

Even I am amazed at how shamelessly the financial markets can turn to savage governments that are doing so much to buy them survival time through the credit crunch and recession! Some of this is knee-jerk mindless politicking. How easy to blame governments for the so-called 'mess in which public finances are in', on the one hand decrying historically high government deficit spending while on the other complaining about the threat of higher taxation such as the UK's new 50% higher tax rate for those earning above a quarter of a million and similar higher taxation in the US. What would it be costing those who complain if the governments stuck to balanced budget targets regardless of the underlying recession? There is a cry on many sides for government spending to be cut and tax rates to be lower. We entered the crisis with historically low direct taxes (income and corporation taxes).

Some others decry the 'crowding out' effect of governments mopping up savings by issuing a few trillion of government bonds on top of the trillions of bills issued as swaps for impaired and semi-illiquid assets held by banks to reduce their writedowns and nominal losses, to protect their capital and ensure they can retain basic solvency. Given the highest credit rating of government bonds, however, crowding out is offset by the boost to economic growth compared to what it would otherwise have been (i.e. the money is not lost to the economy, but generates multiplier effects by how it is redistributed) and the Treasury bonds help leverage bank lending and have a very high collateral value to support further investment credit. Productive investment is made more by those who borrow than by those with surplus savings. Hence, the 'crowding out' view should be replaced by a 'crowding in' theory of government borrowing. There is not a simple correlation between money supply statistics and government borrowing, certainly not one that can persuade me of the simple axioms of classic monetarist precepts.

But, the reality for clear-thinking economists is that lower government spending would not help the economy anyway, not the 'real economy' so-called; it would today just make the whole of the 'economic cake' smaller and postpone recovery, possibly propelling the world's leading economies into Depression (up to a decade possibly of zero, negative or low growth as Japan in the '90s, or longer, as applied economists know, The Great Depression of 1873-1896).

But, the reality for clear-thinking economists is that lower government spending would not help the economy anyway, not the 'real economy' so-called; it would today just make the whole of the 'economic cake' smaller and postpone recovery, possibly propelling the world's leading economies into Depression (up to a decade possibly of zero, negative or low growth as Japan in the '90s, or longer, as applied economists know, The Great Depression of 1873-1896). I can only characterise fiscal consrvatives and 'small government is better government' pundits as blinkered, unable or unwilling to see and take responsibility for the big picture! Adam Smith's 'invisible hand' hypothetical and subjective proposition was not that everyone's selfishness should be as narrowly and individually focused as possible to produce the maximum inadvertent public economic and charitable benefits. That would be patently absurdist, since it can only be obviously true that extreme selfishness would undermine national economic integrity, and similarly at the global level; income and wealth is ultimately a social product, dependent on the quality and integrity of the total system, not of each part acting independently.

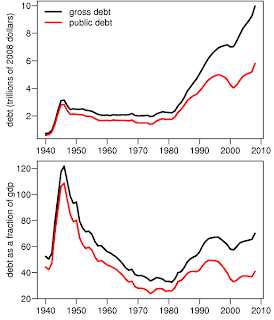

The famous national debt clock in New York shows the gross debt figure, but over a third of this is are obligations between arms of government, not tradable Treasury bonds, much of which in my view should be made tradable and sold into the secondary bond market and the proceeds used to finance social programs and a large part of the budget deficit without thereby increasing the gross national debt.

The internal government part of the national debt is shown by the gap between red and blue lines. In other OECD countries this debt that is internal to government is typically about 20-25% of gross national debts.

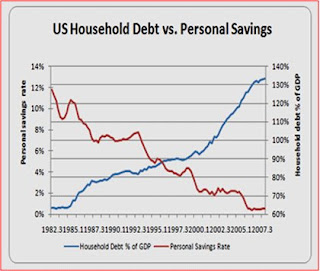

The internal government part of the national debt is shown by the gap between red and blue lines. In other OECD countries this debt that is internal to government is typically about 20-25% of gross national debts.Except for the USA in recent years unless we look only at its publicly held debt which has remained fairly constant, many governments held the line in maintaining a fairly constant gross debt ratio over the last decade, the private sectors, banks, businesses and households more than doubled their debt ratios to GDP in credit-boom high trade deficit countries. But, without that the trade-surplus countries could not have maintained their growth. Indeed, it was a boon to many emerging markets. But now we see export-led economies recessing faster than deficit-led economies. An exception to prove the rule is the Bush strategy from 2001 onwards when government tax cuts and cuts in social programs, with Adam Smith's 'invisible hand' in mind as prescribed by monetary conservatists, helped secure recovery but in a severely unbalanced way that proved to be relatively 'jobless' compared to more conventional fiscal recoveries.

The private sector should not complain now when the public sector has to do substantial borrowing now. And it is very likely, anyhow, that government deficits and debt ratios may fall as ratios to GDP sooner and faster over the medium term (3-5 years) than private sector balances, especially as it turns out that much of the financing bail-out of banks proves to be profitable for taxpayers - even if taxpayer money is scarcely involved in the bail-outs.

I know it is hard for taxpayers to understand that their money is not what the government is playing with in its liquidity windows and treasury bills for bank asset swaps. They readily confuse government budget deficits with bank bailouts. The two things are not the same. Government budget deficits are almost entirely fiscal responses merely to recover economic growth, not to recapitalise or restructure the banks directly.

I know it is hard for taxpayers to understand that their money is not what the government is playing with in its liquidity windows and treasury bills for bank asset swaps. They readily confuse government budget deficits with bank bailouts. The two things are not the same. Government budget deficits are almost entirely fiscal responses merely to recover economic growth, not to recapitalise or restructure the banks directly.Had governments been less prudential over the past 20 years and done more to rein in asset bubbles, property, credit markets, including most importantly the banking bubble where banks stocks grew to dominate a quarter of stock markets and nearly half of quoted compnaies' profits, then the crisis today would be less severe.

Many commentators are now talking of the Treasury Bubble as the next bubble after

the dot-com, housing, mortgages, commercial real estate, private equity, and hedge fund bubbles. This is nonsense. We can see clearly that when government takes on the liabilities of the banking sector that there is a massive net reduction in credit insurance; the government credit risk spread goes up a few tens of basis points, but private sector and banks credit risk spreads fall by hundreds of basis points.

Commentators are happily getting on their high horses about investors chasing long-term Treasury prices to loftier and loftier levels only now to find this bubble too is leaking air fast like previously emerging markets, commodity prices and oil last year, and so on. This is not the same. The demand for government paper has utility and necessity; it is not just a speculative bubble.

Long bond futures fluctuate. They may have fallen 20bp — from 143 mid-December to 123 yesterday and yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury Note from 2.06% to 3.11% — up 51% with technical levels all over the place, but this is just to be expected camera-shake.

There is also some staking out the market in advance of the large government auctions expected monthly this year. It is not a case of too much supply and not enough demand driving prices lower, at least not anywhere except at the long end simply because at first sight very long term paper seems unnatractive at current historically low coupon rates. This does not mean that the current volumes of government borrowing are more than the markets can willingly even hungrily absorb. All that is happening is that government is testing the outer limits before settling on the optimumally cheapest maturities they can get away with.

UK and US Treasuries are also buying in their own bonds, so-called Quantitative Easing, which just looks to me like restructuring their cost of money and reducing the availability of older higher coupon paper by a significant amount to focus buyers who need government paper on new issues. The Fed said at a policy meeting weeks ago that it would buy back up to $300bn, and it didn't alter that target at last Wednesday's gathering.

Critics lambast UK and US treasuries for buying or swapping illiquid and impaired RMBS and CMBS, toxic CDOs, credit card bonds, student loans — to loan money against anything and everything! This is much exaggerated. The Treasuries are charging substantial fees and exerting 25-30% haircuts, leaving themselves with more than adequate headroom to generate substantial medium term profit that I calculate will both finance recapitalisations of banks and pay off half of medium term government budget deficits thus relieving taxpayers of the risk of sharply higher future tax rates. Personally I'd like to see these haircuts translated into lower mortgage debt for sub-prime and other troubled mortgagees.

Some analysts fear all this is dragging down the US dollar, but that correction is welcome and to be expected anyway. However, there is the usual panic reaction too that the U.S. Treasury is borrowing and spending the country into oblivion! That is just absurd doom-mongering when this accusation had been better aimed at the private sector.

Last week US Treasury sold a record $26bn in 7-year notes (reasonable), $35bn 5-year notes, $40bn 2-year notes, to be followed this next week by $71bn in longer-term debt. This all seems very sensible to me. Total net borrowing needs for the second quarter are now $361bn. But, given this is for the current budget year ending September 30 the timing is quite responsible, even if massively up from the only $13bn this time last year and double the previous estimate of $165bn.

Last week US Treasury sold a record $26bn in 7-year notes (reasonable), $35bn 5-year notes, $40bn 2-year notes, to be followed this next week by $71bn in longer-term debt. This all seems very sensible to me. Total net borrowing needs for the second quarter are now $361bn. But, given this is for the current budget year ending September 30 the timing is quite responsible, even if massively up from the only $13bn this time last year and double the previous estimate of $165bn.The rumours are that the US Treasury will sell 30-year bonds every month, and start auctioning 50-year bonds! In the UK long term government bond yields always fall because there is sizeable Life and Pension fund demand. This may now be the case too in the US? The issuance is needed to fund the fiscal-deficit projected to hit at least $1.75tn in 2009 and $1.2tn in fiscal 2010. The importance can be seen in the composition of foreign holders of US government paper.

The high issuance is good news for the economy as the only leverage getting the economy out of the hole it is in, but there is scarcely a news source or market commentary that says so. Negative sensationalism to rattle the cages of investors and persuade them into panic buying of gold or CFDs or Treasury bills and avoid long term bonds. But no investors except those with decades long term liabilities should be buying 30-50 year bonds anyway!

The high issuance is good news for the economy as the only leverage getting the economy out of the hole it is in, but there is scarcely a news source or market commentary that says so. Negative sensationalism to rattle the cages of investors and persuade them into panic buying of gold or CFDs or Treasury bills and avoid long term bonds. But no investors except those with decades long term liabilities should be buying 30-50 year bonds anyway!For more on this see my Obamanomics blogspot. (click to via profile)

No comments:

Post a Comment